Professor Francis Tam (left) and Professor Hongfeng Yang (right)

For as long as humans have existed, they have had to deal with natural disasters: earthquakes, rainstorms, and tropical cyclones are just some of the by-products of a life on planet Earth. But since the Industrial Revolution human activity has led to the intensification of climate change across the planet, and this in turn has led to these disasters becoming ever more severe. Two experts from CUHK’s Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences have examined how our day-to-day life bears upon these extreme events.

Exacerbated by humankind: the human impact of natural cataclysms

Professors Francis Tam Chi-yung and Yang Hongfeng have spent their academic careers looking into the causes of natural disasters, and both their studies, in their different ways, point to the exacerbating impact of human activities on these events.

Professor Tam notes how the various activities of city-dwellers have created the urban heat island effect, where heat generated from urban activity makes the area warmer than surrounding rural areas. ‘If you leave the city, you’ll find that the temperatures don’t rise that high,’ says Professor Tam. ‘Not only does this make cities much hotter, but it also leads to more intense rainstorms due to higher convection rates.’

In recent years, the professor’s research has dealt with the urban heat island effect in the Greater Bay Area, one of the biggest conurbations on the planet and home to more than 86 million people. In 2024, the professor co-authored a paper that delineated the connection between extreme rainfall in the area with the heat island effect created by the GBA, pointing out that, even outside the traditional monsoon period, the industrial activity in the region was on such a scale that urban areas generated enough heat to make rainstorms three times more likely.

The heat generated by urban environments has also led to more intense tropical cyclones. This is a phenomenon driven by the warm water surrounding the immediate vicinity of cities. Thanks to this sudden boost in energy, typhoons have as a result become much harder to predict, and also much more destructive.

Another problem brought on by the urban heat island effect is the increased frequency of ‘hot nights’, where daily minimum temperatures remain at 28°C or above. ‘Hong Kong is a coastal city, and its high humidity in summer monsoon season makes it harder for sweat to evaporate,’ say Professor Tam’s MPhil student, Martin Lau Chung-shing, who has devoted his thesis to heatwave in the GBA. ‘Normal physiological functions are also impaired by prolonged heat exposure or heatwave.’ This is particularly tough on the homeless, who cannot escape the heat so long as they remain outdoors, therefore making them extremely susceptible to heat stroke.

Professor Francis Tam (left) and his MPhil student Martin Lau (right) have studied extreme precipitation and heatwave in the GBA

Human activity also contributes to earthquakes. This may seem surprising, as most of us assume that they occur at random. But as Professor Yang points out, our energy needs have also inadvertently created conditions for earthquakes. Since 2017, his team have been studying induced earthquakes in the Sichuan Basin, the main shale gas production region in China, and found that some induced earthquakes could be destructive. In 2020, his team drew a connection between earthquakes and hydraulic fracturing, a process which involves firing high-pressure jets of water into shale rock to access pockets of natural gas deep underground. The professor explains: ‘With the injection of fluid, the faults [in the rock] will be lubricated, and start to move.’

Earlier this year, the professor’s team released a paper that elaborated this theory, detailing how precursory signals had appeared almost a year before a 2019 magnitude-5 earthquake in Sichuan. The exploration of shale gas reserves in the surrounding area, which had started in 2015, had produced foreshocks as early as October 2018, which then built up until the earthquake occurred eleven months later. At just 4 km below ground, this was an extremely shallow quake––normally, seismic events take place dozens of kilometres underground. The study points to the area’s fracking activities as a substantial contributor to the quake. ‘So human behaviour, especially industrial activities, can induce earthquakes,’ says Professor Yang.

Professor Yang has spent years studying earthquakes and how they can be caused by human activity

Hong Kong has not endured a particularly serious earthquake for more than a century. As a result, most people may not take the likelihood of this type of natural disaster very seriously. Yet Professor Yang cites the 1918 Shantou earthquake, the only earthquake to have caused direct damage in Hong Kong, as a cautionary tale. At that time, buildings at Hong Kong Observatory and St Joseph’s College were damaged, and a general panic spread throughout the city. ‘According to principles of earthquake generation, earthquakes of a similar magnitude may also be generated sometime in the future. It's just a matter of time––we don't know how soon.’

Moreover, as a coastal city Hong Kong is also susceptible to tsunamis that originate from the active tectonic zones scattered around the western Pacific. Although the city is mostly sheltered by its geographical location against bigger-than-normal waves, Professor Yang cites a 2022 paper that notes the possibility that a huge magnitude-9 earthquake in the Manila Trench could produce a tsunami affecting southern China. ‘The waves could be at least a few metres high, so it’s a major threat,’ he warns.

A safe and sound future: preparing for the eventuality of earth-bound catastrophes

As the old saying goes, ‘forewarned is forearmed’, and this also applies to natural disasters with the potential to affect Hong Kong. Recently, Professor Yang has been working on increasing public awareness of how earthquakes propagate through the gathering of near-fault data. Assessment of their causes and impact has until recently been hampered by the inability to obtain this type of data, which allows an accurate firsthand glimpse of seismic processes.

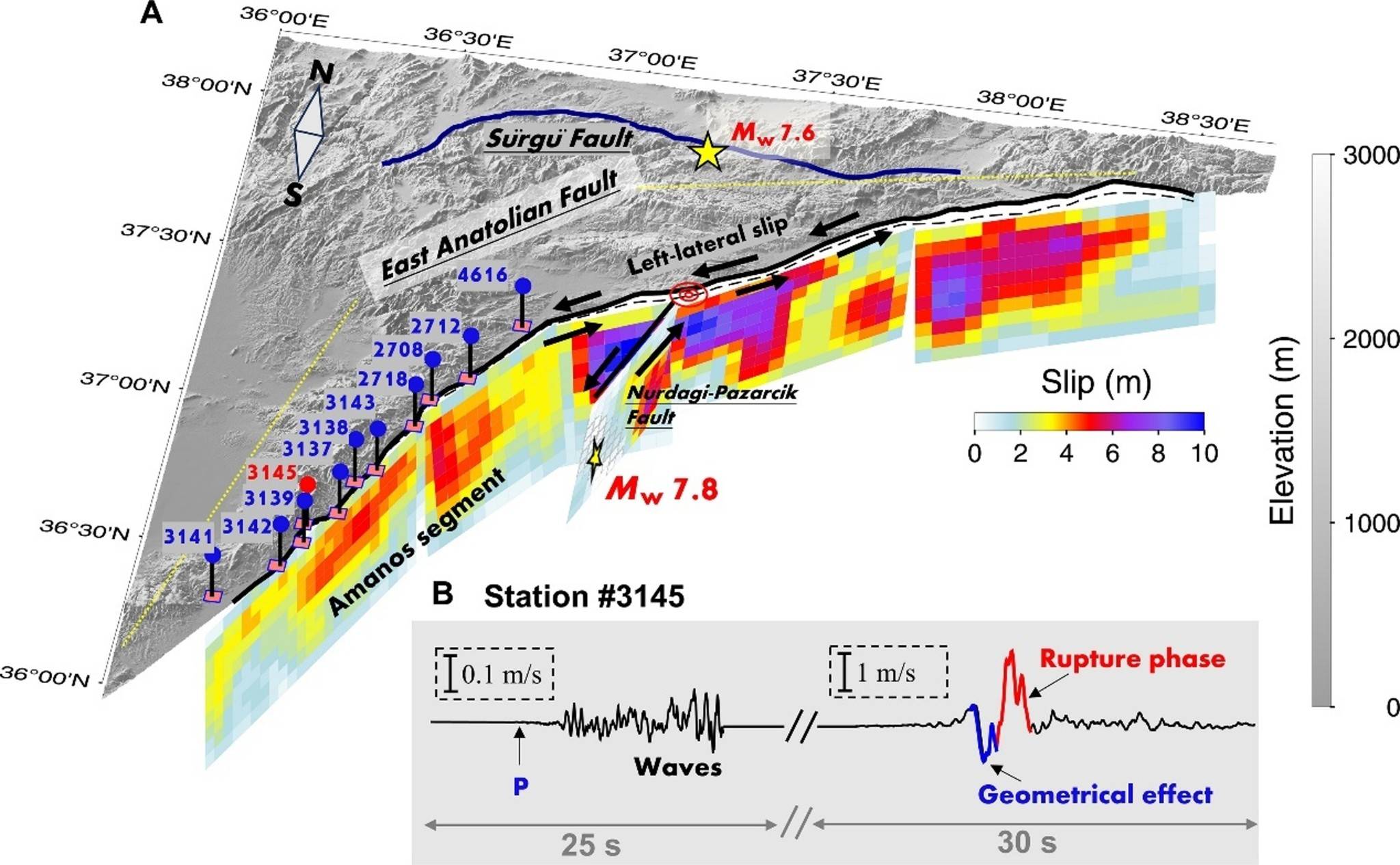

A 2023 earthquake in southern Turkey furnished the professor with reams of material for analyses: with the amount of near-fault data gathered by Turkish scientists and agencies, ‘now we are just “standing” next to it, we are seeing the rupture process directly. So that makes a huge difference.’ Using their near-fault data, his research team has been able to connect the presence of near-fault waveforms with fault ruptures, allowing them to more closely track how earthquakes propagate and affect the Earth’s ground motion. The professor suggests that their analyses will prove valuable in the way we prepare for such natural disasters in future.

Professor Yang and his team has analysed near-fault data from the 2023 magnitude 7.8 earthquake in Turkey to better understand how earthquakes occur

To combat the problems caused by the heat island effect, Professors Tam and Martin have proposed a warning system to combat the effect of typhoons, rainstorms and heat waves caused in Hong Kong. In the former cases, they suggest tailoring advisories to better fit different districts: ‘The Observatory issues the weather warnings, but it’s the Drainage Services Department that deals with the floods. Perhaps some sort of impact-based warning can be developed from this relationship,’ says Martin. He suggests the development of something akin to the Observatory’s Special Announcement on Flooding in the northern New Territories, to warn different districts in Hong Kong about the dangers of imminent flooding.

Martin also has a similar proposal for the problem of hot nights, where the Observatory will produce a ‘hot night warning’ similar to the ‘heat stress at work warning’ introduced last year. In this scenario, when nighttime temperatures exceed 28°C, shelters can be provided for those in need. All these measures and warnings will be helpful in enabling the city to mitigate the impacts brought about by climate change.

At the end of the day, however, the academics agree that future-proofing our city against natural disasters is best done through education. Professor Yang is acutely aware that the relative rarity of earthquakes has led to society neglecting the potential risks. ‘For Hong Kong, the most challenging thing is raising public and also governmental awareness.’ Although it is unlikely that a major earthquake will affect Hong Kong in the near future, he still believes that it would be useful to heighten local awareness of the long-term danger: ‘We should invest, we should get to know better about potential threats and risks, so that we can be better prepared.’

He adds that universities like CUHK are crucial in such efforts, as they engage in research that allows us to prevent and mitigate any potential impacts, and cross-disciplinary studies that will help raise awareness and assist in formulating better societal responses to earthquakes. In doing so, they help to build a more sustainable future, in a city that is resilient to the trials and tribulations offered up by Mother Nature—and turbo-charged by the carelessness of humanity.

Chamois Chui is an editor in the Communications and Public Relations Office, The Chinese University of Hong Kong.